Rethinking I-94

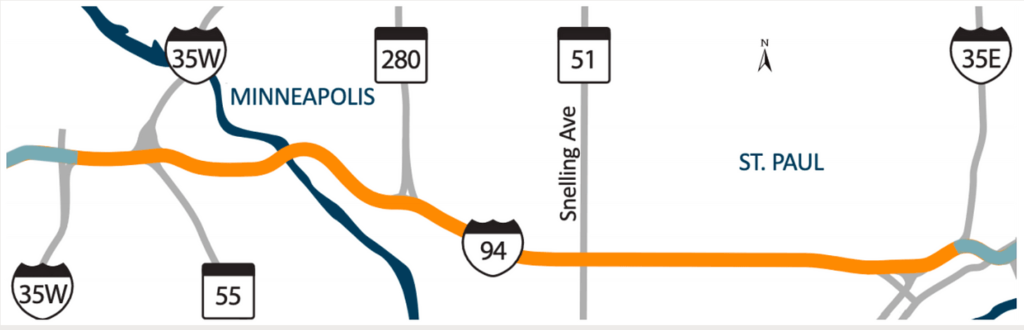

MnDOT has begun planning for the reconstruction of Interstate 94 in Saint Paul and Minneapolis and the Highway 280 interchange. This will be the first major rebuild since the highways first opened in the 1960s.

When I-94 was built, homes and businesses all along the corridor were removed. The heart of the Rondo neighborhood lost 700 homes, 300 businesses and $35 million in intergenerational wealth. In Saint Paul, 1 in 8 African Americans lost a home to the highway. In South St. Anthony Park, the construction of connecting Highway 280 also destroyed hundreds of homes and businesses. Today, harmful emissions from traffic increase risks for asthma, heart disease, and cancer, and the constant noise decreases quality of life in ways we may not even realize.

Highways are built to only have a 50 to 60-year life, and MnDOT is responsible for maintaining the investment made by the federal government back in the 1960s. MnDOT named this planning process “Rethinking I-94.” SAPCC doesn’t believe it’s too much to ask that the 21st century process of looking at a new I-94 and 280 interchange actually reflect that name: rethinking these roadways that did so much damage when they were built and continue to do damage each day.

In late 2020, SAPCC joined 25 other community organizations in signing a community flyer and a letter to MnDOT about the project, calling for a greener, quieter, healthier corridor for the people who use it and live, work, and play nearby. Planning for this interstate highway corridor in the heart of the Twin Cities region should set a new standard for urban transportation projects in the age of climate change.

In February 2021, the Saint Paul City Council passed a resolution strongly opposing reconstruction of I-94 in its current form, and rejecting the addition of any new lanes. The Minneapolis City Council passed a similar resolution. Both councils also asked for transit, pedestrian, and bicycle improvements for corridors over, under, and along the highway, and stated that an extension of the Midtown Greenway from Minneapolis into St. Paul to connect to Ayd Mill Road should be included as part of the project.

Just recently in summer 2021, MnDOT presented an official draft Purpose and Need Statement for the project . This is an important document that guides the planning and project alternatives going forward. Everything else that is decided is compared to that statement, so how it is defined is critical. They are seeking public comments now!

FIND OUT MORE

About the what’s happening now with Rethinking I-94:

- MnDOT’s Rethinking I-94 project page, including the draft Purpose and Need statement, goals, and evaluation criteria. This page includes a link for submitting public comments.

- Community Flyer Endorsed by SAPCC

- Let’s rebuild I-94 in accord with our vision for a better future by Barb Thoman, Union Park Transportation Committee co-chair and Debbie Meister, member of Neighborhoods First!, Villager, Feb. 17 2021

- Saint Paul City Council resolution (February 2021)

- Minneapolis City Council resolution (January 2021)

- Will MnDOT be responsive to communities’ I-94 non-expansion demands? Bill Lindeke, MinnPost, Feb 2, 2021

- Reconnect Rondo Position Paper on Rethinking I-94

About the history of I-94 in St Paul:

- Interstate 94: A History and Its Impact

- Interstate 94: Today and Tomorrow

- Almanac: Remembering Rondo with Marvin Anderson

- MNopedia entry on the Rondo Neighborhood

- Reconnect Rondo: History

About urban highway health effects and what’s being done elsewhere:

Revisiting the Urban Interstate: Freeway to the Future, or Road to Ruin? Video recording of MoveMinneapolis 2021 Transportation Summit, May 18, 2021.

Near Roadway Air Pollution and Health: Frequently Asked Questions. US Environmental Protection Agency, 2013.

Proximity to Major Roadways. US Department of Transportation, 2015.

Traffic, Air Pollution, Minority and Socio-Economic Status: Addressing Inequities in Exposure and Risk. Gregory C. Pratt, et al., International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, May 2015.

“Populations on the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum and minorities were disproportionately exposed to traffic and air pollution and at a disproportionately higher risk for adverse health outcomes. Despite driving less, the air pollution impacts were higher from all sources — especially transportation sources — at non-white and low SES households that tended to be closer to the urban core. In contrast, block groups with more white and higher SES populations, often located outside the urban core, tended to have higher rates of car ownership and to drive more while the air pollution impacts at their homes tended to be lower from all sources. Recognizing these inequities can inform decision-making to reduce them.”

Deconstruction Ahead: How Urban Highway Removal Is Changing Our Cities. Kathleen McCormick, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, April 2020.

Mapping the Effects of the Great 1960s “Freeway Revolts.” Linda Poon, Bloomberg CityLab, July 23, 2019.

“Inside cities, commuting benefits were eclipsed by the negative effects on the quality of life for those who lived near freeways. In city after city, urban highways split neighborhoods, walling residents off behind impenetrable ‘border vacuums’ and creating barriers that blocked communities from accessing opportunities across town. That, in turn, hindered employment and income growth, and made travel within cities more difficult…. Over time, the construction of urban freeways sped population loss and lowered land values in city neighborhoods.”